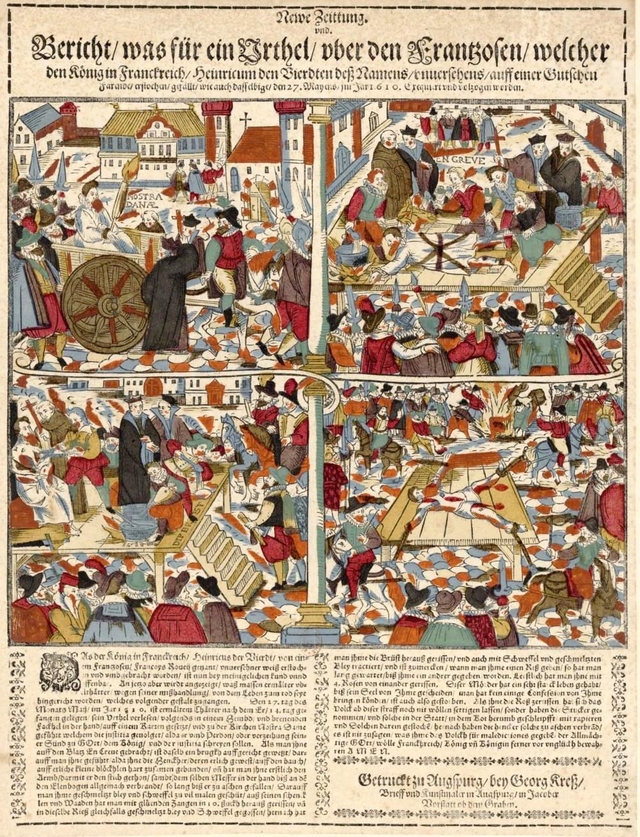

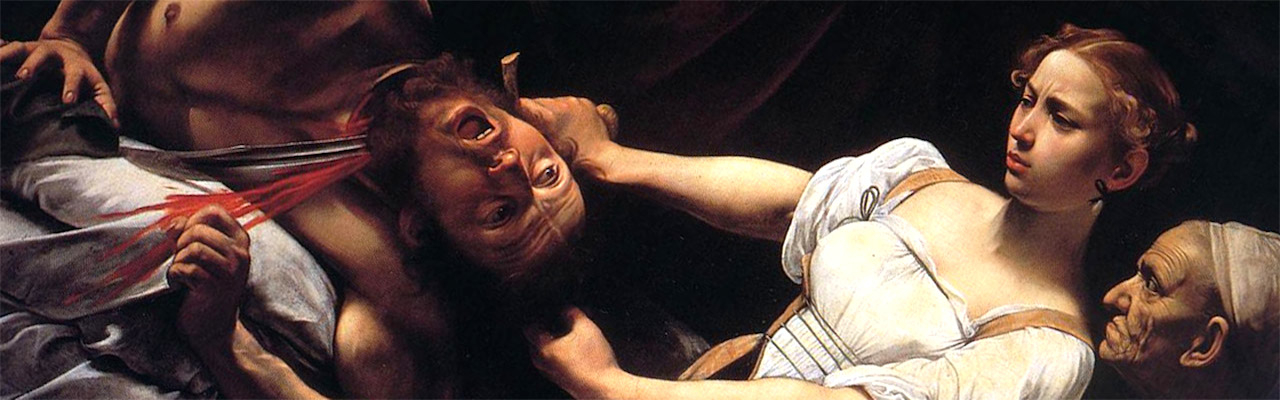

The history of the professional executioner is a chronicle of perfecting the choreography of death. (Painting credit: Caravaggio, Judith Beheading Holofernes, 1598.)

The history of the professional executioner is a chronicle of perfecting the choreography of death. (Painting credit: Caravaggio, Judith Beheading Holofernes, 1598.)

A Short History of the Executioner

Thomas Cromwell stood on the scaffold of Tower Hill.

On a warm July day, he declared to the crowd his intention to die “in the traditional faith.” Cromwell knelt and placed his head on the stone, and the executioner began his work. The executioner, it seems, was having a bad day. Though he had executed Thomas More with a single swing of the axe, for some reason he could not muster that same strength for Cromwell. The executioner made such a scene that sixteenth-century chronicler Edward Hall thought it important to record the grisly event: “[Cromwell] so paciently suffered the stroke of the axe, by a ragged and Boocherly miser, whiche very ungoodly perfourmed the Office.”

Perhaps it’s surprising that a beheading could be too grisly, too spectacularly bloody. An execution is supposed to terrorize; to, as Michel Foucault puts it, “arouse feelings of terror by the spectacle of power.” Though the crowd that had gathered at Tower Hill was prepared for a gory spectacle—they were there, after all, to witness the beheading of a traitor—they were not prepared for the mismanaged scene that unfolded before them. Hall, like most of the executioner’s crowd, would have expected a quick, clean execution. The chronicler’s language is telling: he indicts Cromwell’s executioner not for the killing, but for its particularly shoddy nature. The executioner’s botched job was unnecessarily cruel, not to mention a poor reflection on “the Office.” It seems the executioner’s greatest offense was his lack of professionalism.

The history of the professional executioner is a chronicle of perfecting the choreography of death. It’s a story of exacting skill and the never-ending search for a more efficient means to enact (and contain) the spectacle of death. The professionalization of death—a chilling business—was cultivated for centuries by a profane tribe of men who were denied civil status and ostracized from nearly every aspect of daily life. Forced to live at the margins, the executioner was defined by ambiguities: a pivotal actor in the multipart drama of public killing, an extension of the crown, and yet morally hazy and universally despised.

One did not simply become an executioner; rather, one was generally born into the profession. Though not legally hereditary, the office was usually recognized as a family trade. The title of executioner passed from eldest son to eldest son; younger sons and nephews remained in the family business, filling vacancies in other cities or working as assistants. Daughters of executioners invariably married sons of executioners, therefore providing an endless bounty of death’s choreographers.

Thus the genealogy of the executioner, much like any European royal dynasty, can be drawn as a continually intermarried family tree: the Sansons served through the downfall of the French monarchy and into the reign of Napoleon; the Reichharts survived Weimar politics to work for both Adolf Hitler and the Allied Forces; and the Pierrepoints are synonymous with capital punishment in Britain. If the father died before an heir came of age, something akin to a regency was established. In 1741, Jean-Baptiste François Carlier was appointed executioner of Nantes at the tender age of three months.

If the office of executioner was bound by a kind of primogeniture, it was because the families had few alternatives. The very presence of the executioner and his family in everyday society was so feared that their lives were highly governed. Early modern cities enacted laws dictating nearly every aspect of the executioner’s life, from where he could live to which buildings he could enter to whom he could touch.

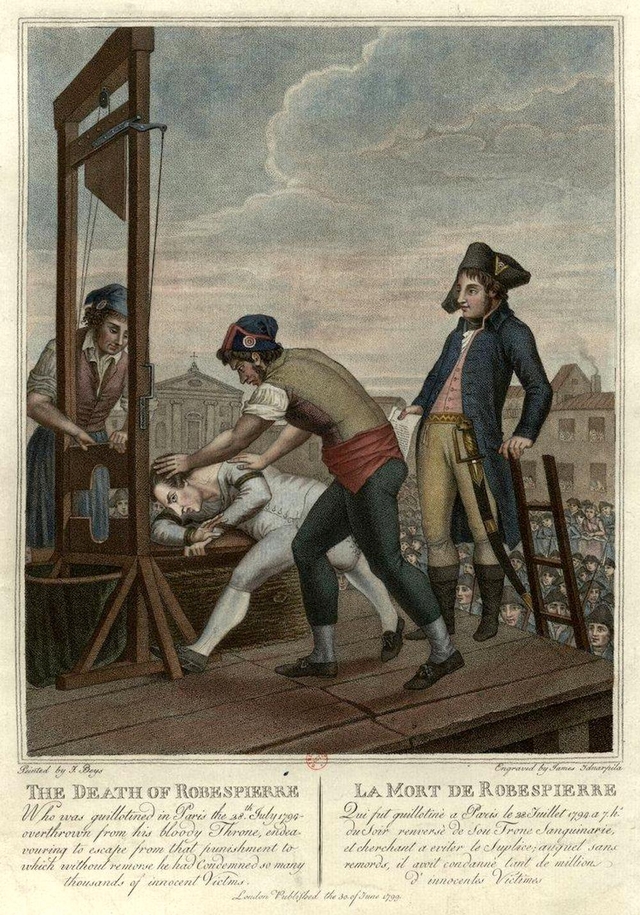

Engraving after a painting by J. Beys, Death of Robespierre: Who was guillotined in Paris the 28th July 1794, 1799. Bibliothèque Nacional de France (BNF)

In most of Europe, executioners were prohibited from living in the urban areas they served. Apart from required attendance at church services, where they and their families were restricted to a designated pew, executioners only entered the city to perform tasks relating to their office. Those entailed the duties, of course, of torturing or killing the condemned, but they also included a variety of basses oeuvres with peculiar perks, such as the exclusive right to clean cesspools (and any valuables contained therein), the right to claim stray animals, and ownership over animal carcasses (and hence their profitable hides) that might litter the streets. Included in the basses oeuvres was a management role over other social pariahs, from whom the executioner could levy a tax, suggesting that he was a sort of sovereign of the underworld. In sixteenth-century Troyes, the executioner collected a one-time fee of five sous from prostitutes and one liar from lepers.

But if the dirty work of scavenging lined the executioners’ pockets, then the droit de havage (literally the “right to dip into”) made them wealthy. Droit de havage entitled executioners to portions of goods and produce from nearly every vendor in the marketplace and each cart that passed through the city gates. Such a bounty of food and wine was meant to ease the ostracized lives of the executioner and his family, to provide them with financial comfort where there was little other comfort to be had. No doubt it earned the scorned group even more scorn; many citizens assumed that the executioner took lives as casually as they took havage. It certainly didn’t help that the droit de havage, a de facto tax, was a right shared only with kings.

Executioners were not, as is sometimes assumed, boorish uneducated sociopaths who took pleasure in the killing and the limelight. Rather, they were largely literate and well-educated. Their education, like most tradesmen, was practical in nature. They were largely taught at home since executioners’ families were forbidden from attending school (as a boy, Charles-Henri Sanson attempted to attend school but was expelled after a classmate recognized his family). An executioner’s education entailed a rudimentary knowledge of his locality’s justice system, order and rituals, as well as his role within them.

Most importantly, the executioner’s education included extensive instruction in human anatomy. Indeed, the executioner’s knowledge of the human body was so renowned that their services were often demanded in place of a physician. The author of a 1908 entry in the British Medical Journal noted, “On July 24, 1579 a license was issued by Frederick II to Anders Freimut, executioner of Copenhagen, granting him the right to set bones and treat old wounds though he was expressly forbidden to meddle with recent wounds,” adding that “in 1695, Andreas Liebknecht the Copenhagen executioner, was in such repute for his treatment of the venereal disease that he wrote a book on the subject.”

While the executioner’s knowledge of anatomy engendered these ironic side jobs, it was acquired with a singular purpose: efficiency. Each was judged on his meticulous ability to carry out a death sentence while avoiding the excessively bloody spectacle of a botched execution. Public executions—by sword, fire or wheel—were the culmination of a theatrical performance through which the crown enacted its deadly authority. The performance of justice needed to be seamless enough to appear natural—any disruption might be interpreted by the gathered crowd as an intervening act of God, a repudiation of the divine rite of kings. Hence it needed to be expertly enacted. To botch the highly choreographed routine was seen as an affront to justice.

To botch could also be life-threatening. In some German towns “an executioner was permitted three strikes (really) before being grabbed by the crowd and forced to die in place of the poor sinner,” Joel F. Harrington notes in his book, The Faithful Executioner. Though never written in law, most cities throughout France were similarly intolerant of a botched execution. To avoid becoming victims of their audiences, executioners sought out the most efficient means of swift death. Frantz Schmidt, sixteenth-century executioner of Nuremburg, boasted in his journal that he successfully abolished the traditional punishment of drowning women convicted of infanticide in a sack in the local river. Schmidt replaced the archaic punishment with beheading, arguing that it was more economical and a deterrent to women who might have been plotting a similar crime.

Likewise, in the midst of the French Revolution, as Charles-Henri Sanson struggled to keep up with death’s high demand, he warned the 1791 National Assembly that beheading by sword was an inexact skill. “Swords,” he noted laconically, “have very often broken in the performance of such executions.”

The heavy workload had already cost Sanson his younger son, Gabriel, who upon displaying a decapitated head slipped in its pooling blood, fell from the scaffold, and met an untimely death. Afterward Sanson became one of the most vocal advocates for of Joseph-Ignace Guillotin’s new invention, calling it a “fine machine.” Sanson tested the new-fangled death machine on live sheep and calves, then on the corpses of women and children. During his trials he found the cuts of the machine were not as clean on male corpses, and his observations prompted a redesign. Only after Sanson declared himself satisfied with the redesign did the guillotine become synonymous with the French Revolution. It was with that machine that he would execute thousands of citizens, including Louis XVI and Charlotte Corday.

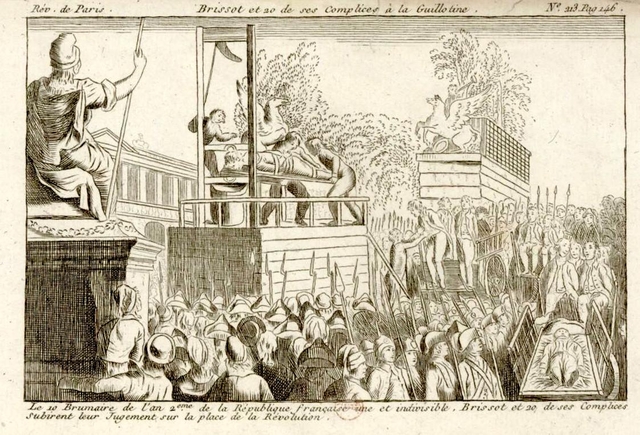

Brissot et 20 de ses complices à la guillotine [“Brissot and twenty of his accomplices at the guillotine”], 1793 BNF

The invention of the guillotine forever changed the nature of executions. As technological innovations often do, it eliminated the human hand and snatched the art of killing away from the executioner. The assembly line-like nature of the guillotine, its ability to execute hundreds in a single day without human fatigue or error, made the executioner an automaton, a simple button-pusher. The executioner became a near-relic; there was no longer any need for a highly-trained executioner who benefited from years of accumulated family knowledge. By the nineteenth century, the ostracized dynasties of Europe’s executioner had been all but disassembled.

There were hold-outs, of course, Albert Pierrepoint continued his family’s work in England, but his work was not nearly as spectacular as his forefathers’ had been. He maintained the executioner’s professionalism, outlining the exacting techniques he employed to make his hangings as smooth as possible—from “a rehearsal” to exhaustive measurements of the condemned—but if Pierrepoint had botched his work, there would be no threatening crowd to take notice.

Pierrepoint’s work was done in private, hidden behind the grim walls of the country’s main prison. Great Britain outlawed public execution in 1868 (though France would not outlaw public executions until the twentieth century, executions were moved from public squares to the prison courtyard making them harder and harder to witness). It’s hard to say why the public had lost its taste for the executioners’ meticulous work; perhaps it was a hangover from the bloody spectacles of the French Revolution, perhaps it was the privatization of the nineteenth century, with its preference for the warm corners of domestic drawing rooms. Perhaps the guillotine’s mechanization of death seemed too easily brutal.

Engraved by L. Massard, L’exécuteur des hautes oeuvres sous Louis XV (époque de Charles-Henri Sanson), from the book Les Français sous la Révolution, 1843. Wikimedia Commons

The office of executioner was slowly phased out after World War II. As moral economies of punishment shifted, deterrence and reformation began to vie with one another. And after the requisite war criminals had been tried and executed, reformation triumphed and European nations began outlawing capital punishment. The last of his kind, Pierrepoint, happily left his family’s work behind him in in 1956 (the United Kingdom would abolish the death penalty in 1969), opened a pub and wrote an autobiography. “I do not now believe,” he wrote in his 1974 memoir, Executioner: Pierrepoint, “that any one of the hundreds of executions I carried out has in any way acted as a deterrent against future murder. Capital punishment, in my view, achieved nothing except revenge.”

What remains of the history of the executioner is his professionalism; his ability to efficiently manage the spectacle of death, to make his work seem like justice’s natural route, and to above all avoid disruption or botching. Like the throngs that gathered to witness the work of Charles-Henri Sanson or the beheading of Thomas Cromwell, we do not question the executioner’s purpose—to kill the condemned—only the cruelty of his methods.